Chris & Allyson vs. Italy & Croatia (June-July 2019)

Croatia Day Eight: Zagreb '80s Museum, Naive Art Museum, Homeland War walking tour, urban beach party

Each of us copes with birthdays in our own way. My wife, a model of dignity and grace, discreetly spends hers on an international vacation whenever possible. In 2019, she started her next orbit of the sun in the Zagreb Westin, snuggling with the man she settled for in 2010. He hadn't appreciated her expensive tastes back then, but it is something you get used to.

There wouldn't be a party this birthday, and you do get fewer birthday calls when you're half a world away. The goal was simply to enjoy a leisurely day in Zagreb, and pray desperately that British Airways didn't spoil the party.

An agenda is a birthday gift you give to yourself, and we had one: We'd be visiting the '80s museum and the Naive Art museum, then (in the light carefree spirit of all birthdays) taking a walking tour focused on the Croatian Homeland War. Ha ha ha! Reasonable readers would pin the last item on me, but it was actually something Allyson booked, and when the birthday girl wants a two-hour lecture on ethnic strife, that's what she gets.

Birthday breakfast was muffins at a bakery / coffee-to-go joint, plus the first birthday shots — in this case cappuccinos. We sat on a bench in Zagreb's horsey square — every respectable European city has one — to dine. And then it was back up the side of the hill, meandering around the neighborhoods. After a few minutes, we got our bearings and were finally able to walk directly into the past.

The Zagreb '80s museum is, very simply, an apartment decorated in the style of 1980s Yugoslavia. Marshall Tito never practiced the worst brand of Communism, but even his light touch couldn't erase the worst of that system. When he died in 1980, Yugoslavian society started to thaw in exciting and dangerous ways. Western pop culture and consumer goods started infiltrating the city.

The museum allows one to swim through that chaotic mess. You can try on clothes, lounge on the furniture, read 1980s newspapers, watch 1980s TV, look at 1980s smut and (theoretically, if the machines are working) play 1980s video games. There’s a living room, a kitchen and dining area, a bedroom and an office space. As an added bonus they have half a 1980s car — sadly, not a Yugo — deposited in the entry hall. Traffic was light during our visit, so we had ample opportunity to model the clothes, leaf through the smut and contemplate how Communism was ultimately destroyed by wide neckties. Let a thousand flowered sports shirts bloom.

We could have wallowed in capitalism's triumph for hours, but furniture from the 1980s isn't particularly comfortable, nor are 1980s newspapers particularly informative. The smut is certainly acceptable, but it pales in comparison to the next wonder that awaited us: the World's Shortest Public Funicular.

Back in time, at the '80s museum.

We never go out of style ... at the '80s museum.

A view from the world's shortest funicular.

DO be naive! At the Naive Art Museum.

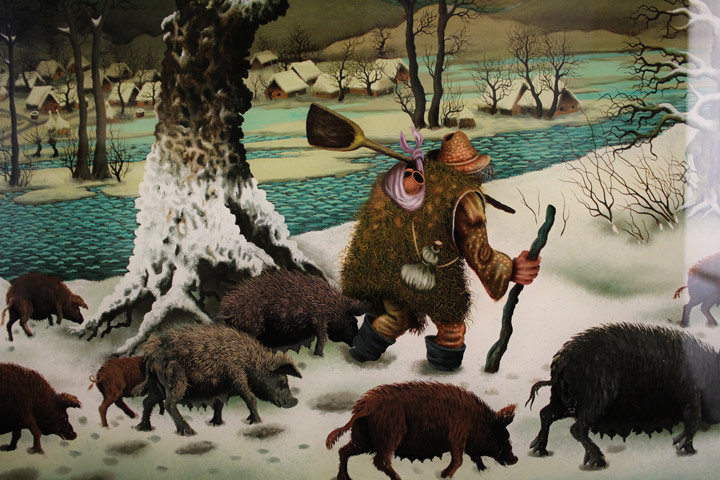

One of the Naive Art Museum's masterpieces.

Some context: Funiculars are an important element of Jaffe-White vacations. We cherish unusual modes of transportation, and funiculars are perhaps the rarest; diagonal railroads are among man's greatest achievements. We have risked life and limb on the world's steepest funicular (in Australia), ascended to the heavens in Budapest, and glided to the heights of Pittsburgh and Johnstown.

The hills of Zagreb are not particularly brutal, but in the late 1800s, the city installed its monument to laziness. The Zagreb funicular connects the lower town and the promenade right above Artpark that we had seen the day before. As we left the '80s, we were already halfway up the hill, but no self-respecting citizen of the world would pass up a chance to experience the engineering marvel of the Balkans.

The ride cost 85 cents and lasted 35 seconds. But perhaps there is no way to quantify the gratitude one feels as he slips the surly bonds of earth, rising upward, ever upward, or at least for 35 seconds, to be deposited on a street where he could have walked quite easily.

As we were now at the summit of Mount Zagreb, our next destination was mere steps away. The Naive Art Museum, lamentably, is not filled with paintings of young adults who think that hard work and honesty are the way to get ahead in life. But it does have value nonetheless. The Naive school consisted of artists with less formal training, creating works that are often pastoral or simplistic. It's a notch above folk art, and the good people of Croatia simply adore it. I am pleased to report that they are not wrong.

The museum spans seven or so rooms, in a building across the street from the museum of Broken Relationships. Most of what we saw was oil on glass, or oil on canvass, with bright colors. Most of the artists were named Ivan, and they doted on country life, nature scenes and religious themes. Naive art really pops, in a way that's more cartoony than real. Our approval was marked by the highest of honors: two refrigerator magnets were purchased in that gift shop.

As we were now one step closer to becoming authentic Zagrebians, a celebratory lunch was in order. We walked down the steps to Artpark, ducked into the tunnel system and popped out on the east side of the hill. The web app "Happy Cow" suggests vegetarian-friendly restaurants around the world, and it steered us to Gajbica, where we sat outside and consumed enormous salads and vegan cake. All this took an hour, and at its conclusion we headed toward our secondary dessert: a lecture on ethnic strife.

The Croatian Homeland War started at the horsey statue, as many respectable European walking tours do. It was less of a sightseeing tour, as the stops weren't particularly distinct. It was rather an ambulating history lesson. Lessons are only as good as their teachers, and we had the great fortune of wandering the streets with a young man named Vid. Born in 1991, he was only a baby during the war's ugliest episodes. But he did a remarkable job establishing the context for the ethnic tension, then explaining why it exploded after the fall of Tito. Some hasty notes:

Ethnically speaking, "Croatian" is a fuzzy term. The Croats were under the thumb of the Serbs and Bosnians, who had more of a Turkish bent, I gather. We began at a statue of Stjepan Radic, the founder of the People's Peasant Party in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. This delightfully named entity — a bougie Peasant Party would never do — was waving the banner of an expatriate king who had been stashed in England. Radic firmly believed that Croatians needed more hegemony within the kingdom. He was a persuasive and charismatic man, but he shared the tragic flaw of so many great men: he was not bulletproof. A Serbian radical murdered him, which historically speaking tends to lead to racial strife. Religious differences — Serbs are Orthodox while Croats are Catholic — didn't help.

The tunnels running underneath upper town.

No European city is complete without a horsey statue.

Checking out a bomb shelter on the Homeland War tour.

Wrapping up at the "beach" -- a book festival in a city park.

History has a cute way of coming full circle, and by the middle of the 20th century the Croats had become the cruel dictators. A fascist government under Ante Pavelić found good friends in Hitler and Mussolini, and dabbled a bit with the concepts of ethnic cleansing. Never mind if your own ethnic group is a bit muddled; you can still insist on three generations of "purity" if it means payback for the Bosnians.

After World War II, the region found a happy medium in Tito, a dictator for all seasons. The good marshal papered over ethnic strife with the notion of improving all of Yugoslavia; for good measure he kept a respectful distance from Stalin, allowing for a warm-and-fuzzy, progressive form of Communism with less state control. By finding the balance point between East and West, and doing business with both, Tito strengthened Yugoslavia's economy far beyond those of its neighbors. Awash in their fancy $1,500 cars and hot Communist fashion, the people of Yugoslavia let ethnic strife lower to a simmer.

Tito was egregiously mortal, however, and this fine state of affairs could not survive his death. After a decade or so, Croatians were agitating to leave Yugoslavia — a referendum was involved — while ethnic Serbs living in Croatia were not on board. The Yugoslavian military was mostly Serb-controlled, so the newly independent Croatia was in immediate peril. After a mad scramble to obtain weapons and get their share of loyal army troops in place, a defense was pieced together. The war was on.

Vid walked us into the tunnels, designed for World War II air raids to protect upwards of 3,000 people. They saw use again in the Homeland War. He showed us a basement bomb shelter in a typical residence. There we watched a video that explained the general advance of the conflict on Zagreb, and later Dubrovnik. There were propaganda clips from each side, claiming the other was ethnic cleansing. And there were commercials for war-related children's toys, and rock videos meant to inspire people to fight.

The tour concluded at a quiet indoor memorial to those killed in one of the most heinous attacks of the war: when Serbians dropped cluster bombs on downtown Zagreb, at lunchtime, on a weekday. For his part, Vid said younger generations have a difficult time understanding the ethnic strife — it seems to be a relic of the past, and because so many Serbs left Croatia after the war, the day-to-day friction may have lessened. But he felt it was real, and could return.

This was all standard relaxing birthday fare, so we kept the vibe going by enjoying one of the parks near where the cluster bombing happened. There were no signs of the attack. Rather, a Croatian publishing company was hosting its annual "beach party," having festooned the area with enormous jellyfish umbrellas and lounge chairs. Mini public libraries abounded, allowing anyone to grab a book, sit back and read. Our Croatian isn't so good, so we had an excuse for just relaxing. The native Croatians had no excuse, but in a show of solidarity with their American friends, they also chose not to read. In the spirit of international friendship, Allyson and I split a dessert pancake and soaked in the ambiance.

The day was, for the most part, over. After a pit stop at our hotel, we found an Indian restaurant for the vegetarian birthday girl. We sat outside and watched the crowds, then hustled back toward the hotel as spitting rain began to materialize. Briefly, we poked our nose in a punk bar lauded in some of the guide books. But it was ridiculously smoky, and one virtue of having birthdays is that you can reach an age where you're tired of such things. So instead it was back to the Westin, where complementary birthday cake was waiting.

Italy was done. Croatia was done. Our vacation, as planned, should have been done. But detours do work out sometimes.